reaction-diffusion

In the last years of his life, Alan Turing was working on a problem in biology: how plants and animals can grow into complex shapes. His paper on the subject was published in 1952, the year he was arrested and tried.

In the last years of his life, Alan Turing was working on a problem in biology: how plants and animals can grow into complex shapes. His paper on the subject was published in 1952, the year he was arrested and tried.The key idea was called reaction-diffusion: chemicals inside cells react with one another and also travel across the cell walls, diffusing to neighboring cells.

These processes cause the levels of the chemicals in each cell to fluctuate. But while you might expect the levels to blur themselves out, Turing showed that certain combinations were unstable and would tip into one of two extreme states. And since neighboring cells would necessarily have similar levels due to diffusion, the result was that patterns could spontaneously form and remain stable, even from a random initial state. Below is a video of spots forming in a two-chemical system that Turing proposed:

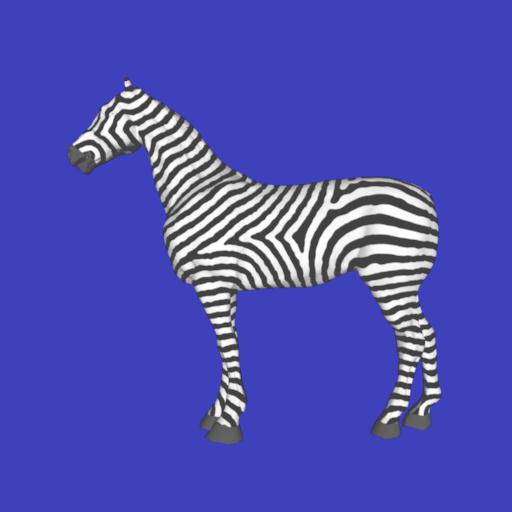

The image on the right shows the result of another reaction-diffusion system running on the surface of a 3D zebra model, making highly plausible stripes. Click through for other species.

The image on the right shows the result of another reaction-diffusion system running on the surface of a 3D zebra model, making highly plausible stripes. Click through for other species.Not only does Turing's idea explain leopard spots and zebra stripes but it also suggests a possible mechanism for the formation of internal organs and the arrangements of leaves on plant stems. Pretty much everything in the development of plants and animals perhaps.

And yet there was a problem. Turing's work was far ahead of its time, well before any of the chemicals that were supposed to be at work could be identified. The theory even fell into disrepute when it was applied a little too keenly to discoveries in fly embryo development and was later found not to be relevant. But finally, in 2006, a paper discovered some of the genes responsible for the even distribution of hair follicles on mice, and found that Turing spots were indeed being used.

A few more examples of reaction-diffusion systems are below. The first shows turbulent patterns in the FitzHugh-Nagumo model. You can see waves of red being chased by tails of green-blue. Where the red gets ahead it spreads out. Where the green-blue catches up it swamps the red. These are the two chemicals in action.

Another example shows a semi-stable line spreading out tendrils in a labyrinth pattern. Here the parameters are such that the two chemicals are evenly balanced, with just a little spreading allowed.

One of the most interesting systems is the Gray-Scott model. With certain parameters the Turing spots actually divide and spread:

This looks so much like a bacterial colony it sends shivers down my spine. Keep in mind that there's no life here, nothing that is copying itself and growing. It's just the varying concentrations of two chemicals. You could zoom in as far as you like but there's nothing else to see.

To explore Gray-Scott further, there is some excellent work here:

http://www.mrob.com/pub/comp/xmorphia/

All of these systems can be explored in an open source package I've put together here:

https://github.com/GollyGang/ready

Thanks to Greg Turk and others for making code available.

This post was originally on LiveJournal.